Ears are amazing: they transform sound waves into brain signals that allow us to hear the world, and they are critical to our sense of balance.

But how many of us have had ear pain, muffled hearing, a child who was tugging at their ear, or ear popping or ringing? So much of our ear is actually inside of our skull, which makes it hard to know what is a normal or abnormal feeling just by looking at the outside part of the ear.

We are often asked to look at a patient’s ear to check for an ear infection. But what exactly are we looking for when we peak into the ear with our otoscopes?

Ear anatomy

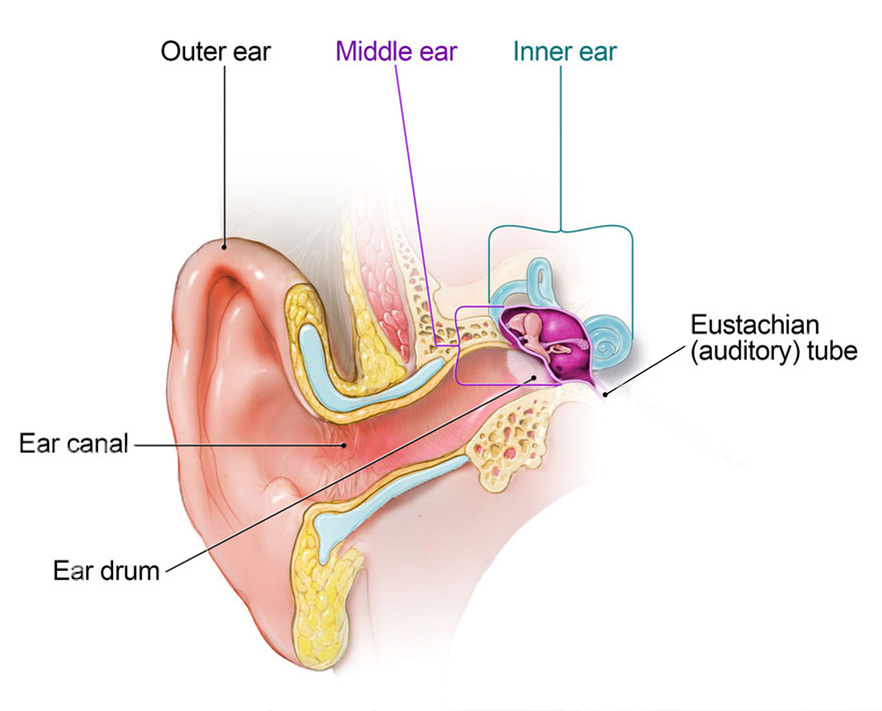

It helps to see a picture of the parts of the ear that are not visible from the outside. There are three major parts of the ear: the outer, middle, and inner ear.

Ear anatomy, Source: CDC

The long tube from the outside part of the ear (pinna) to the ear drum is the outer ear.

On the other side of the ear drum is the middle ear: a small, open space with some important bones that transmit sound from the ear drum to the inner ear. Note the drainage pipe out the bottom of the middle ear (the eustachian tube) this will be important later.

The inner ear looks like shell and a slide from Wild Waves stuck together. These contain the balance sensing organs, and the nerves of the ear that transmit signals to the brain.

Outer ear infections

Many people have had swimmer’s ear or have heard of somebody using ear drops to help with inflammation or an infection of their outer ear. This is called otitis externa. The skin that lines the external auditory canal can get inflamed, infected, or irritated just like any skin of our body.

Because the skin is infected or irritated, we can usually use topical antibiotics (sometimes combined with a steroid) in the form of ear drops to treat the problem. Sometimes the infection has spread too far and we may need to use oral antibiotics.

Outer ear infections often come with discharge from the ear. And because the skin of the ear is infected, it can be very painful to touch the outer part of the ear.

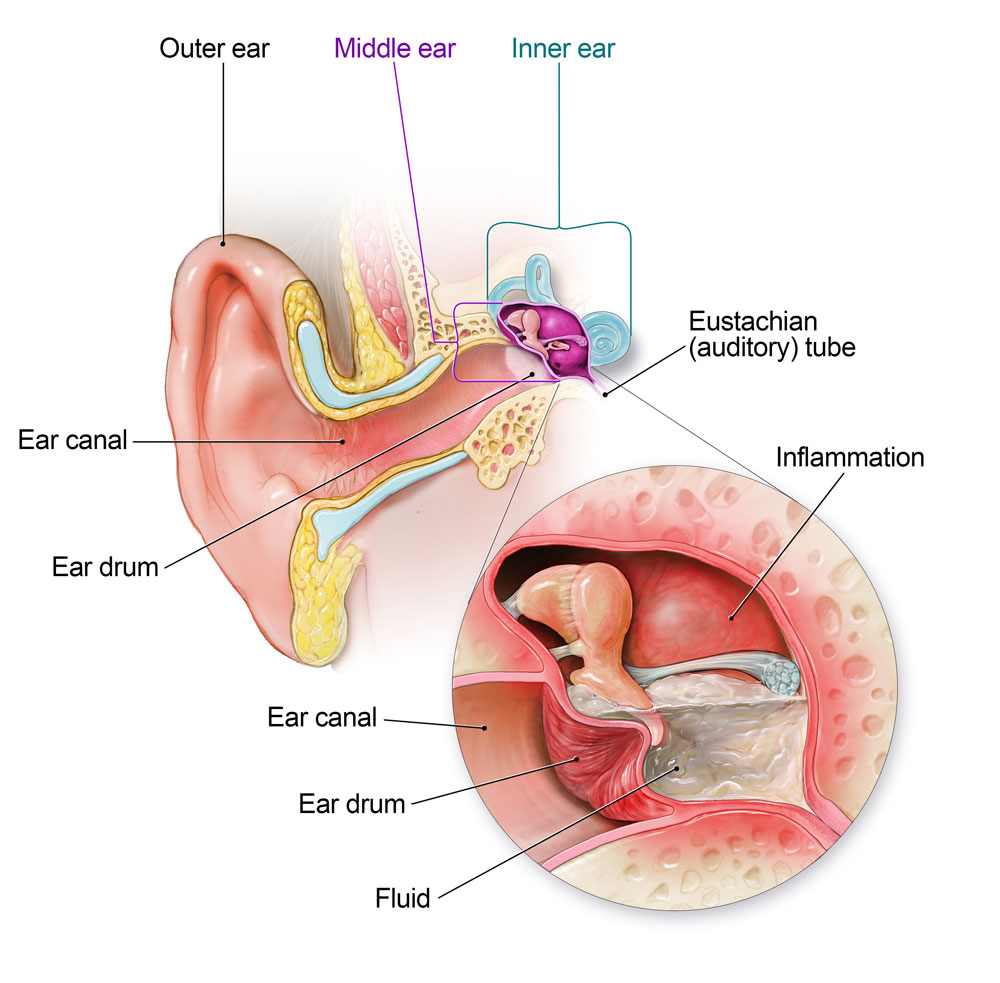

Middle ear infections

Infections of the middle ear occur when fluid builds up in the empty space behind the ear drum. The skin of the middle ear is like the moist surface on the inside of our mouths, and this moisture drains out the eustachian tube into the back of our throat. When this tube gets clogged the fluid created in the middle ear builds up. This fluid can cause pressure to build up on the ear drum (leading to muffled hearing or possible rupturing). Stagnant fluid can become infected with bacteria. Fluid behind the ear drum is called an effusion. Not all effusions are infected, though we do want that fluid to drain eventually because the presence of fluid can affect hearing.

Signs that pediatricians look for to know that the fluid is infected are:

- Bulging of the ear drum

- Intense redness of the ear drum

- An opaque yellow/white color to the fluid

Infection of the middle ear, Source: CDC

Sometimes there is fluid or mild inflammation of the ear drum but no bulging or pus visible behind the ear drum. In these cases, children can have pain or even mild changes to hearing due to the inflammation, but do not have a middle ear infection, and do not need antibiotics. Ibuprofen (Motrin) and acetaminophen (Tylenol) are great anti-inflammatory medications to help with ear pain regardless of the situation.

Understanding the eustachian tube is really important. Often, middle ear infections follow after a patient has had a cold, or congestion and inflammation in the throat and/or sinuses for a couple days. The congestion and inflammation clog the end of the eustachian tube that empties into the back of the throat.

The eustachian tube is prone to clogging in children for several reasons: in a smaller head/body, the angle the tube lays at is very sharp and can kink easily; the space in the back of the throat is smaller in children; and the tonsils and adenoids are relatively large in children under 5 years old, which then get swollen with colds and plug the eustachian tube.

Antibiotic choice (if your child needs antibiotics)

When your provider sees a middle ear infection that needs antibiotics, the first choice is amoxicillin because it will kill the most common bacteria that infect the middle ear. Sometimes there are resistant bacteria, so we need to use antibiotics that overcome this resistance. Generally, we estimate that your child should start to feel better after 24-48 hours of antibiotics. But sometimes we need to reassess, so communicating with your provider is important. Always finish the full course of antibiotics. Your provider will consider your antibiotic history, allergies, and ear infection history when determining which antibiotic to use.

Ear tubes

Sometimes, patients have recurrent ear infections or effusions because their eustachian tube is chronically clogged. In some cases, an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeon will place tubes in the ear drum that allow fluid to drain from the middle ear the outer ear. There are strict guidelines to help determine if this kind of surgical intervention is needed. Your provider will help you determine if seeing an ENT surgeon is appropriate.

Related Stories